Is This the End of Climate Groupthink?

Net Zero is far from being the only manifestation of groupthink, but it is probably the costliest and long overdue for being consigned to history.

We all know that groupthink is a bad thing. It discourages or punishes questioning voices and prevents decision makers from considering alternative options. Such alternatives could end up being cheaper, more effective and faster to implement.

Without critical challenge, risks and unintended consequences are not fully understood, such that projects are delivered late, have huge cost overruns and can even make the problem being addressed worse. Think diesel gate.

The problem is that once any group starts moving in one direction, silence is read as agreement, creating a false impression of consensus. Group membership can provide a psychological feeling of well-being – who doesn’t like being in a like-minded group? However, cohesive groups tend to be over-confident in their views which helps to explain why projects can get out of hand without anyone in the group realising.

Many practical approaches have been developed to tackle groupthink, but they tend to slow delivery and increase upfront costs. In my own industry of IT, most large projects have both a range of user representatives on the team as well as a separate, completely independent software testing team. This approach can deliver a better system and by adopting a right first-time approach, the overall cost should be lower.

However, it’s very rare to see such active approaches built into, say, government policy development. Politicians come into power with a manifesto to deliver, though this may be a naïve viewpoint! Therefore, they are not naturally inclined to bring on board advisors who disagree with them. Politicians prefer to present a united front, with dissent seen as a weakness.

Often, there is time pressure on making policy decisions. Groupthink, though increasing risk, seems more efficient. In public life and in board rooms, loyalty and solidarity are highly prized. For something like Net Zero, there’s also international signalling. Governments want to be seen as “leading,” which reinforces conformity across countries.

Since Brexit, groupthink has become embedded in all aspects of society. Unfortunately, I see this all the time. Friends and relatives with different political views either shake their heads at my dubious thinking or get emotional and even angry when I try to suggest there are different ways to look at issues.

These days there is no meaningful debate across the floor of the House of Commons. There is much less meeting of minds and only increasing levels of antagonism between the different parties. Demonstrating my own groupthink, I am bound to say that the left generally seems more intolerant. I have never thought of myself as someone on the right – more a classical liberal. However, it does seem that, when I wasn’t looking, the country slid quietly to the left, leaving me and many others stranded. What’s going on now seems to be a long overdue and inevitable correction.

Groupthink has been understood for many years and there are studies of classic examples, such as the Bay of Pigs invasion, the Challenger disaster and 9/11. However, I believe that Net Zero will one day be viewed as the single most significant example of groupthink ever, on a scale approached only by what happened during the response to the COVID pandemic. It’s hard to deny that we are still feeling the economic shock of lockdown policies but Net Zero is much more pernicious and long lasting.

It ought to be a truism that without cheap reliable energy, a society cannot prosper. Yet Net Zero persists as a policy to address climate change without any consideration of the alternatives or the deep societal costs it inflicts. Why is this?

Groupthink and the Climate Consensus

Net Zero is a policy response to a so called Climate Emergency, first called Catastrophic Anthropogenic Global Warming (CAGW). I first became aware that CAGW was an issue as a doctoral graduate student around 1987. It has gestated and evolved since then, to become a quasi-religious belief system.

The consensus around climate change and Net Zero has a different quality, and more nuance, than the media would have you think. I don’t believe that there is a conspiracy on either side of the argument. There are no single movements pushing in either direction, either for or against the consensus and the policy that arises.

Rather, there are many different groups supporting the existence of a climate emergency. This ranges from people who are genuinely worried about a warming planet to those who don’t believe (or even care) if it is warming – but they can see obvious ways to exploit the concerns of those who do. Renewable energy companies are obvious examples, but there are many others, such as the large banks that make carbon trading possible and profit handsomely from the activity.

However, there are many people in the middle ground. Determining Net Zero policy from partially understood science, involves huge unknowns. This is why latching onto a single narrative (“this is the path”) reduces anxiety and gives a sense of direction for most people. The policy direction has largely been accepted as settled doctrine across mainstream parties, business lobbies, NGOs and most of the mainstream media.

Practically, dissenting voices are often framed as denialist or obstructive, which suppresses genuine debate about costs, trade-offs, or alternative strategies. This can mean risks, such as higher energy bills, industry offshoring and grid instability, don’t get fully stress-tested until they materialise in practice.

The good news is that we are at last seeing a push back. The Reform UK party is completely committed to rolling back Net Zero policy. Even the Conservatives, under Kemi Badenoch, have announced that they would repeal the Climate Change Act of 2008 – first introduced by Ed Miliband.

The question is what is driving this change in stance on Net Zero?

Unsurprisingly, the answer is “money”!

In their recent report Britons’ attitudes to high energy bills: the permacrisis that keeps burning, the polling company More In Common found that:

Three quarters of Britons are concerned about their energy bills this winter and 60 per cent don’t think energy bills will ever become more affordable.

Concern over winter energy bills extends far beyond those traditionally seen as vulnerable and only drops among those on a household income over £100,000. For all other income bands at least two-thirds of Britons are concerned.

Britons have little confidence in the government to reduce bills - 43 per cent either believe the government has no plan or one which is making things actively worse.

Financial worries and concerns about energy bills are driving Labour’s poll woes - among those concerned about the size of their winter bills Labour is retaining just 57 per cent of its 2024 voters.

And this from an organisation that says about its Net Zero policy:

The climate crisis is the most urgent threat for society today. As an organisation we take this threat extremely seriously and want to ensure that More in Common plays its part in reducing its impact on the environment.

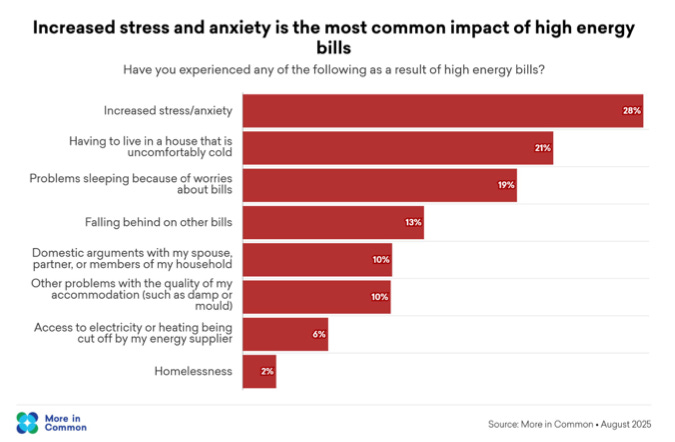

The report also highlights the most significant impact being on mental health:

Tellingly, many focus group participants said that:

…fuel poverty isn’t something they had experienced before and so to now be unable to heat their homes has made them feel they are going in backwards in life, not progressing.

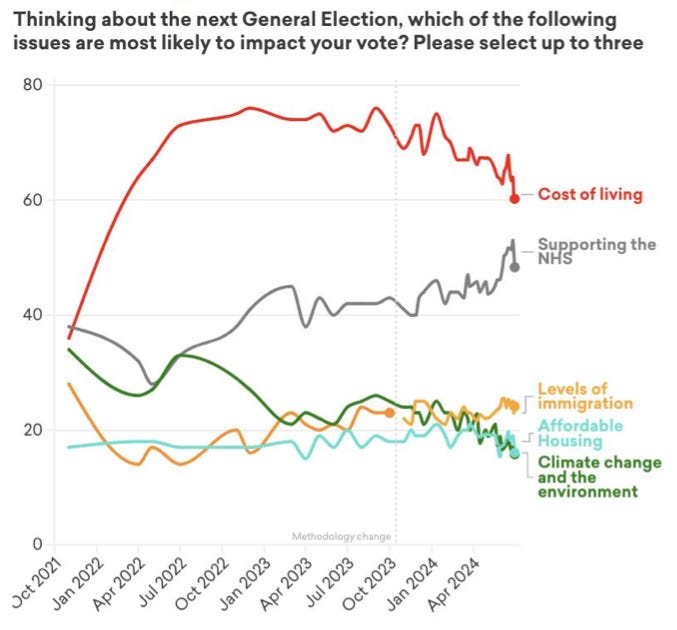

You can see this reflected in More in Common’s Climate and Energy at the 2024 General Election and beyond report in conjunction with E3G. Concern about climate change displays decreasing relevance as people find it difficult to heat their homes (see chart below). The key lesson to learn from charts like this is that although most people are concerned about climate change, more practical considerations dominate.

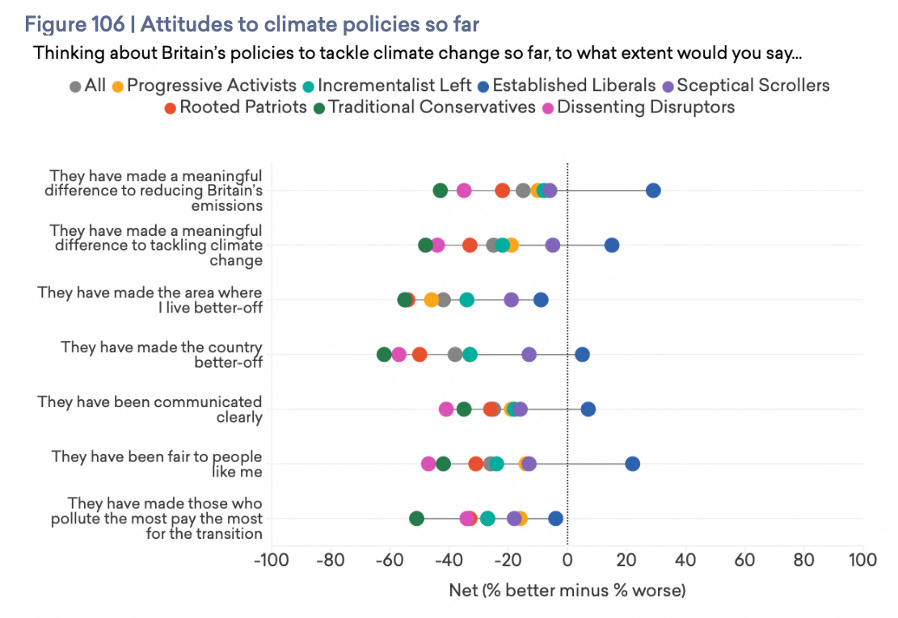

In their July 2025 report Shattered Britain, More in Common found that climate policies meet almost universal disapproval:

Climate science reappraised

Alongside these changes in public perception, the change of administration in the US has led to a complete re-examination of climate science and the development of climate policy. This has been driven by the recent report A Critical Review of Impacts of Greenhouse Gas Emissions on the U.S. Climate, prepared for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Climate Working Group (CWG). The authors are 5 distinguished PhD climate scientists: John Christy, Judith Curry, Steve Koonin, Ross McKitrick, and Roy Spencer.

Some of the key findings include:

Elevated carbon dioxide (CO2) levels enhance plant growth, contributing to global greening and increasing agricultural productivity

CO2 acts as a greenhouse gas but the research literature shows evidence that emissions scenarios overstate the likely future emissions trends.

There are several dozen climate models which show a large range of sensitivities. Global climate models generally run hot leading to exaggerated projections of future warming.

Most extreme weather events in the US do not show adverse long-term trends and tide gauge measurements show no acceleration in sea level rise beyond historical average rates.

Natural sources of climate change have been underplayed in attribution studies.

Significantly, it is likely that the economic damage from climate change is likely to be far lower than forecast previously.

Overall, any changes in US policy actions are expected to have unmeasurable impacts on global climate.

The report hasn’t gone without criticism but as far as I can tell much of the criticism is aimed at discrediting the scientists involved and spurious arguments about cherry picking data. Having followed all the authors since I first took an interest in this subject, I have always found them to be knowledgeable, sincere and professional.

Conclusion

Groupthink is a well-known behaviour that leads to poor decision making, increased costs, delayed implementations and unexpected consequences. Despite this it is widespread in public policy making and boardrooms. Worse, it is deeply ingrained in how social attitudes are formed and maintained.

Of all the major examples of groupthink that I have come across, the climate consensus is the longest running and the most pernicious in its detrimental impact on society.

The good news is that the consensus on climate change is breaking down, and it is only a matter of time before policy makers have to admit that they were wrong in pushing Net Zero at any cost.

The bad news is that there is still time for our Energy Secretary, Ed Miliband, to sanction even more unaffordable spending commitments which will be very difficult to unwind by future governments. Time is already running out for when the “about turn” needs to happen if we are to avoid wide-spread blackouts.

It looks like the Reform UK Party will be in power after the next election, but the Conservative and Labour parties will have left them with not only the biggest ever economic black hole, but also the most insecure power system in modern times. Lead times for reliable gas fired power stations are typically 6-8 years whilst in Norway political concerns about high energy costs there mean they may soon not be a source of backup energy.

Therefore, we have to be realistic about how long it will take any future government to unwind years of disastrous energy policy. The sooner the next election comes the better.