Why the Renewables Industry Loves LCOE

But what aren't they telling us?

When the conversation turns to clean energy, there’s one number that gets quoted over and over again. It’s the Levelised Cost of Energy (LCOE) and is regularly held up as the way to compare energy sources. LCOE is a neat, single figure that tells you how cheap, or expensive, electricity is to produce over time.

But what does it really measure? And why does the renewables industry love it so much?

What is LCOE in detail?

The Levelised Cost of Energy is a metric used to estimate the average cost of generating one unit of electricity. It is usually expressed in dollars or pounds per megawatt-hour (MWh) over the lifetime of a power plant. It takes into account:

Capital costs (the upfront expense of building the project),

Operating and maintenance costs,

Fuel costs,

And the total electricity generated, all discounted to reflect the time value of money.

Therefore:

LCOE = Total Lifetime Costs ÷ Total Lifetime Electricity Output (discounted to present value)

It’s designed to provide a like-for-like comparison between energy sources. In theory you can compare a gas plant with a nuclear reactor or a solar farm.

But does it really do that?

Why It’s Popular with Renewables Industry

The renewable energy industry loves LCOE because it plays to their strengths:

No fuel costs: Unlike fossil fuel plants, wind turbines and solar panels don’t need gas or coal to generate electricity.

Until recently, declining capital costs: The cost of renewables, particularly solar modules, have dropped and with it, the LCOE. However, in recent years costs have started to rise.

Low maintenance: Once installed, renewables are said to run cheaply for decades.

The result? Renewables often appear as the cheapest source of new electricity in LCOE comparisons, especially in sunny or windy regions.

But Here’s the Catch

LCOE has major limitations:

It ignores when electricity is generated. Solar is great at noon, but what happens when the sun sets and demand peaks?

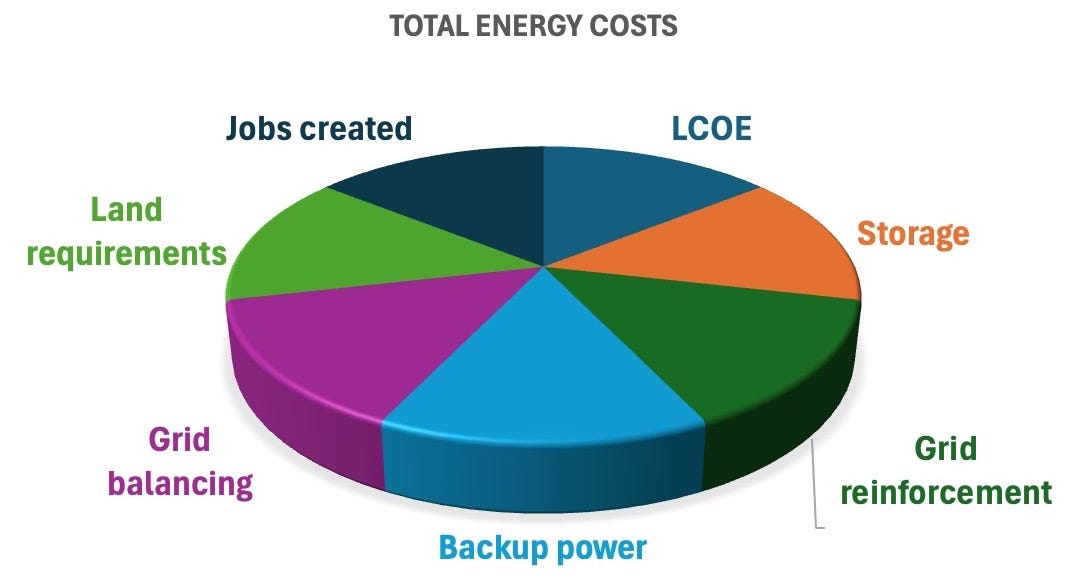

It doesn’t account for intermittency. Wind and solar are variable. LCOE doesn’t include the cost of backup power, storage, or grid balancing. These are large and increasing costs. Storage is increasingly regarded as impractical on a grid scale as well as being expensive. It also comes with its own environmental issues.

It treats all electricity as equal. But electricity has more value and is regarded as higher quality, when it’s available at the right time and place.

It takes no account of relative land usage, with both wind and solar requiring significantly more land.

Quantity and quality of local jobs are ignored. Traditional power requires significantly more engineers and other highly skilled jobs for operation and maintenance. Paradoxically, LCOE sees this as a benefit, completely ignoring societal costs of fewer high-skilled jobs.

That’s why many analysts are turning to more nuanced metrics, like the System LCOE, levelised value of energy, or marginal abatement cost, which try to factor in grid integration and reliability.

So What Should We Make of It?

Proponents of renewable energy use LCOE extensively, but it only tells a small part of the story.

There is no escaping the fact that the grid needs to be powered to a large extent by reliable base-load power. We can debate the proportion, but the problem is that if we don’t subsidise renewables they simply won’t get built.

So the question is - are we prepared to pay for that?

Further reading

I wrote a short metaphorical article which helps explains the fundamental problem of intermittency.