Adaptation to climate change won't cost the earth

Comparing the costs and practicality of climate adaptation with Net Zero

Foreword

To be clear, I accept that many people are concerned about our changing climate and a sizeable proportion believe that there is an actual climate emergency. Rather than argue about this, I want to explore whether the billions of dollars being spent globally on projects like Net Zero in the UK, could be better spent on adapting to climate change.

In doing so I will draw on sources that in most cases are supportive of there being a climate emergency. My main argument is that throwing more money at Net Zero is not going to change the climate. Worse, money spent on Net Zero could be spent in other ways, more efficiently and with more immediate impact.

I will try to show that adaptation policies can be implemented quickly and locally, so that we are not dependent on what other countries do. Adaptation is also an opportunity to create more employment in the UK, being much less reliant on importing foreign made renewable technology.

The High Cost of Net Zero: Why Renewable Energy Policies Fall Short on Climate Goals

For those deeply concerned about the dangers of climate change, the push for Net Zero, particularly in the UK, appears to be a decisive step toward saving the planet. The UK’s commitment to achieving net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, enshrined in the Climate Change Act 2008, has been hailed as a global model, galvanising over 140 countries to set similar targets.

However, a closer look reveals that Net Zero policies are unlikely to deliver meaningful climate benefits while imposing staggering economic and societal costs. These issues are not unique to the UK. They apply globally to any nation pursuing similar strategies. Moreover, governments often obscure the true financial burden of these policies, which are set to escalate further. Even the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change in their report Reimagining the UKs NetZero Strategy, sounded the following warning:

The economy, and ultimately the climate, are not served by setting unrealistic targets that we don’t meet.

In contrast, practical climate adaptation strategies could address climate challenges more effectively at a fraction of the cost. The report also stated (emphasis added):

Reforms should include increasing the overall climate-finance target, deploying funds more quickly, boosting finance aimed at de-risking climate projects, and enhancing the focus on urgent adaptation and disaster recovery needs.

The UK’s National Infrastructure and Service Transformation Authority report UK Infrastructure - A 10 Year Strategy emphasises the need for clear resilience standards (61 mentions), which could be implemented swiftly compared to decades-long energy transitions.

The Promise and Pitfalls of Renewable Energy Policies

The UK’s Net Zero Strategy, detailed in documents like Build Back Greener and Powering Up Britain, emphasises a rapid shift to renewable energy sources such as wind, solar, and bioenergy to decarbonise the economy. The government aims for 100% zero-carbon electricity by 2035, with renewables like offshore wind targeted to reach 50 GW by 2030. In the UN report Renewable energy – powering a safer future, supporters argue that renewables, which emit little to no greenhouse gases, are critical to reducing carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions.

At the same time, the impact of these policies on global climate is negligible. The UK accounts for less than 1% of global CO2 emissions. Even if it achieves Net Zero, the reduction in global temperatures would be unmeasurable. Globally, emissions are rising rapidly in developing economies like China and India, which rely heavily on fossil fuels. For example, China’s coal consumption continues to grow, dwarfing the UK’s emissions reductions. China is therefore already a "clean energy superpower" built on the back of a fossil fuel driven economy.

Any nation following the UK’s path faces the same reality. Unilateral action has minimal impact on global climate outcomes unless major emitters follow suit. As I have discussed before, no-one else is following UK climate leadership.

Moreover, renewable energy systems are not as “green” or efficient as portrayed. Wind and solar power are intermittent, requiring fossil fuel backups or expensive storage solutions like batteries to ensure grid stability during low-generation periods. The Climate Change Committee (CCC) notes risks in scaling up renewables due to planning delays, grid connection issues, and auction design flaws. Proponents of renewables have pointed to metrics such as Levelised Cost of Electricity (LCOE) showing that renewable costs are lower than fossil fuel power. However, the Department for Energy Security and NetZero (DESNZ) - quoted in the House of Lords report: Renewable Energy Costs - explained:

A plant built a long distance from centres of high demand will increase transmission network costs, while a ‘dispatchable’ plant (one which can increase or decrease generation rapidly) will reduce the costs associated with grid balancing by providing extra power at times of peak demand.

These challenges increase reliance on gas-powered plants, undermining emissions reduction goals. Globally, countries like Germany, which heavily invested in renewables, still depend on coal and gas to stabilise their grids, illustrating the limitations of this approach. This understated summary from the World Energy Report highlights the issue:

While Germany’s clean energy leadership is undisputed, the country faces challenges in balancing supply and demand due to its reliance on intermittent wind and solar power. Additionally, integrating renewable energy into the grid and expanding battery storage capacity will be crucial in maintaining stability as coal plants are retired.

Here in the UK last year, Sky news reported that government ministers claimed UK faces 'blackouts' without new gas-fired power stations. Just this month The Telegraph reported Miliband to unleash new gas plants to back up patchy wind and solar. This demonstrates that intermittent renewables are not yet ready to supply a reliable electricity grid on their own. We can not escape the fact that operating redundant systems is inherently more expensive.

The Soaring Costs of Net Zero

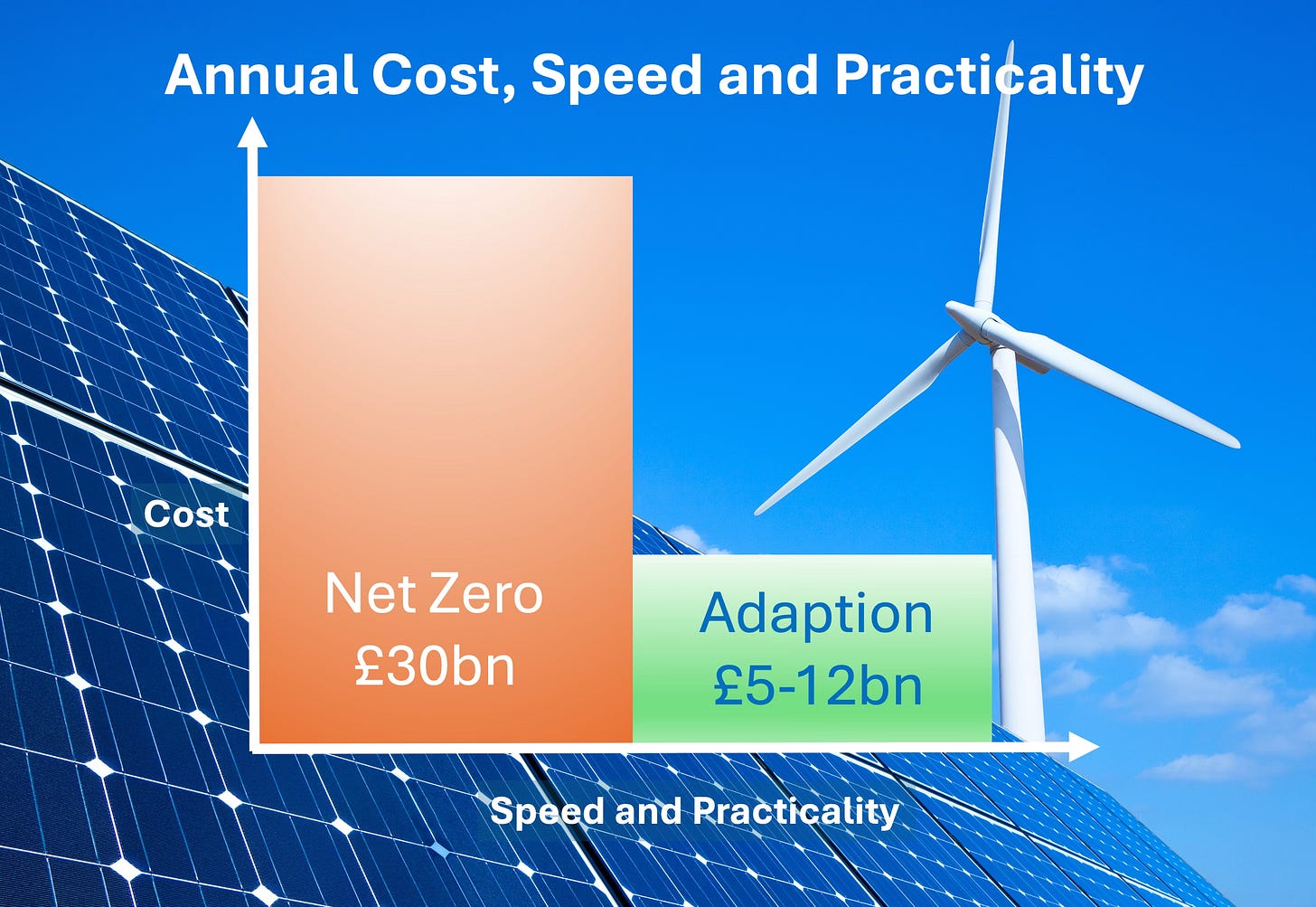

The financial burden of Net Zero is immense and often downplayed by governments. The UK Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) just reported that achieving Net Zero could add £30 billion annually to public spending, equivalent to 21% of GDP in debt by 2050. This is 50% higher than they estimated in an earlier report in 2021. Imagine what the forecast might be in 2030? If you want to dig further into these costs I wrote about this in Britain's Looming Fiscal Storm.

The OBR explains that fuel duty losses (as we switch from combustion engines to EVs) are a significant driver of the costs. I have already discussed Kathryn Porter's analysis into the direct factors contributing to these increasing costs:

Fundamental incompatibility between renewables and our existing grid infrastructure.

Grid instability and blackout risk rises due to lack of inertia which requires expensive and imperfect solutions to compensate.

Environmental levies and carbon taxes.

The existing grid infrastructure is old and requires extensive upgrades to handle renewable energy generators which require relatively more wiring than conventional power stations.

Kathryn estimates that since 2006, £220 billion has been spent on decarbonisation efforts that have provided no economic benefits. This means the total annual costs for subsidies, environmental levies, and carbon taxes are £17 billion per annum and increasing, with almost all of this added to electricity bills. This figure is consistent with the OBR figure of £30bn annually, since it is an average over the period to 2050, growing to £45bn per annum by 2050.

These escalating costs strain economies without delivering proportional climate benefits. As well as these cost drivers, long lead times and excessive regulation mean that 2030 targets are wholly unrealistic.

These costs and challenges are not unique to the UK. Any country scaling up renewables faces similar expenses: building and maintaining infrastructure, upgrading grids to handle intermittent power, and subsidizing technologies that remain costlier than fossil fuels in many contexts. For example, the International Energy Agency (IEA) suggests that while direct renewable costs are falling, global commodity price spikes in 2022–2023 kept solar and wind less competitive than anticipated. The United Nations reported that developing nations, with limited resources, face even steeper challenges, often requiring external financial support to transition.

Governments rarely communicate these costs transparently. In the UK, the DESNZ provides limited public breakdowns of subsidy impacts or long-term grid investment needs. The CCC’s 2024 Progress Report criticizes the government for slow progress and policy rollbacks, such as exemptions from fossil fuel boiler phase-outs, which obscure the true scale of investment required. Globally, political narratives often emphasize the “affordability” of renewables while ignoring system-wide costs like storage, grid upgrades, and backup generation. This lack of transparency erodes public trust and hinders informed debate.

Worse, as we discussed earlier, costs will rise. The CCC estimates that 75% of future emissions reductions must come from harder-to-decarbonize sectors like transport, buildings, and industry, requiring expensive technologies like carbon capture and storage (CCS) or hydrogen. This also ignore the problem that neither of these technological approaches are proven. As the Clean Air Task Force pointed out last year in their report A solutions-based approach to the UK’s net-zero transition:

Simultaneously, expansion of variable renewable technologies will require an unprecedented number of spur lines to be developed. Without adequate proactive commitments for grid tie-ins, variable renewable developers are unlikely to develop projects at the pace and scale necessary to meet the UK’s climate goals.

Therefore, grid expansion to accommodate doubled electricity demand by 2040, driven by electrification of transport and heating, will further inflate the indirect cost of renewables. And this is to say nothing of the massive demand that would arise from a major investment in AI data centres.

Climate Adaptation: A Pragmatic Alternative

Instead of pouring resources into Net Zero’s uncertain outcomes, climate adaptation offers practical, cost-effective strategies to address the impacts of climate change already occurring. Adaptation focuses on resilience to protect communities, infrastructure, and ecosystems from rising temperatures, extreme weather, and sea-level rise. The CCC’s 2024 report notes that the UK’s Third National Adaptation Programme (NAP3) lacks ambition and clear targets, yet strengthening it could yield significant benefits.

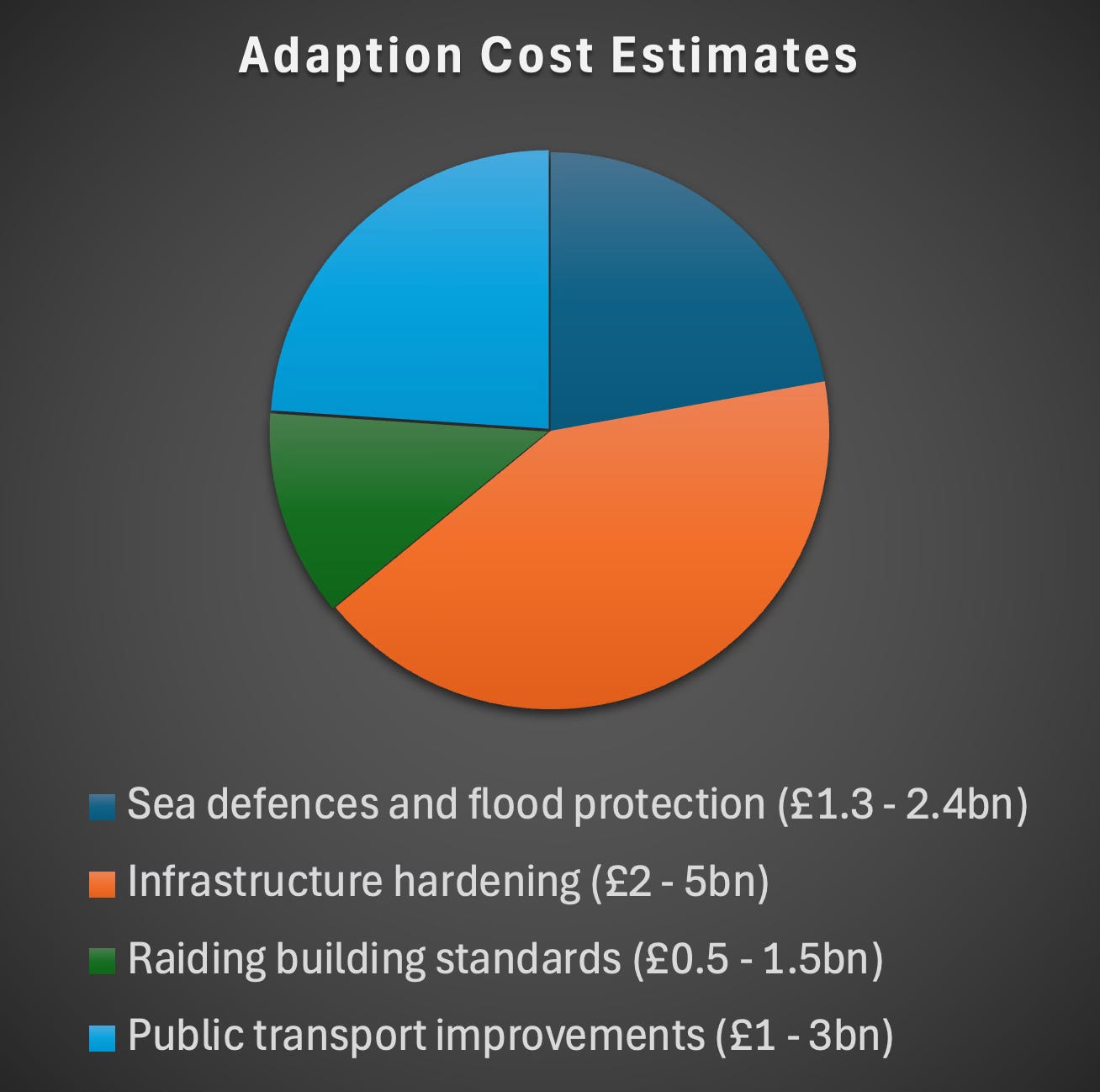

Estimating the annual costs for climate adaptation policies in the UK is challenging due to the complexity of adaptation measures, the lack of centralised data, and the integration of adaptation into broader infrastructure spending. Official sources, such as government reports and the Climate Change Committee (CCC), provide some cost estimates, but comprehensive, disaggregated figures for specific adaptation areas are often incomplete or not explicitly isolated from baseline infrastructure costs.

That said, I have attempted to summarise the available annual cost estimates for the key adaptation areas, drawing from the most reliable data, including government publications, authoritative sources such as the Grantham Institute and climate sympathetic media outlets like the Guardian. These include:

Flood and coastal erosion risk management projects and funding, Environment Agency

Funding for Flood and Coastal Erosion Risk Management in England

Policy Note on Flood and Coastal Erosion Risk Management Spending

UK Chronically Underspending On Climate Change Adaptation Warns Watchdog

What Will Climate Change Cost the UK?, Grantham Research Institute

The estimated figures in 4 main adaption areas are shown in the following chart:

The total estimated annual adaptation investment required would be around £5 - 12bn.

There are many other adaptation measures we might take, though these are likely to be significantly lower in cost. This is partly because they could be implemented as new approaches to existing problems. In many cases it could be cheaper to take action in a climate adaptive way. For example:

Agricultural Innovation: Developing drought-resistant crops and improving irrigation systems can protect food security.

Urban Planning: Green spaces, reflective surfaces, and improved drainage systems can mitigate urban heat and flooding. These measures are localized, scalable, and far cheaper than building new grids or CCS facilities.

Community Preparedness: Early warning systems and disaster response plans can save lives and reduce economic losses from extreme weather.

Comparing this with the OBR figure of £30bn per annum for Net Zero, adaptation delivers tangible benefits regardless of global emissions trends for roughly a third of the investment.

The Global Lesson

The UK’s experience is a cautionary tale for any nation pursuing Net Zero. The focus on renewables ignores the reality of global emissions dynamics, technological limitations and escalating costs.

Governments must prioritize transparency, clearly communicating trade-offs and costs to citizens. Instead of chasing negligible climate impacts, nations should invest in adaptation to build resilience against inevitable climate changes. By reallocating even a portion of Net Zero budgets toward adaptation, we could protect lives, economies, and ecosystems more effectively.

For those who believe in the urgency of climate action, adaptation offers a pragmatic path forward. It acknowledges that climate changes while avoiding the economic and social toll of policies that promise much but deliver little. The UK, and the world, must shift focus to solutions that work before the costs of Net Zero truly cost the Earth.

A request

Please share this article with people you know who are concerned about climate change.

If you can please let me know how they respond:

How many accepted the request to read this article?

How many rejected it without reading?

How many rejected the arguments after reading?

How many read the article and agreed with some or all of the arguments?

Please share your feedback in the comments below.