A Review of ‘Energy Abundance’ the SDP’s Green Paper on Energy

The SDP’s paper shows how to fix our broken energy system but the only party likely to be able to implement it is Reform.

Introduction

The SDP recently launched a comprehensive green paper on their energy policy called Energy Abundance (11th Sep 2025):

https://sdp.org.uk/energy-abundance/

This paper was written by Matthew Kirtley with the help of Alastair Mellon, who is the Social Democratic Party’s (SDP) Regeneration spokesperson. Matthew is a Technology Specialist at Performance Communications. He helps companies communicate complex engineering and economic topics to customers, partners, investors, and policymakers via earned and owned media.

I skip-read this paper when it first came out, prompted by Hilary Salt, the deputy leader of the SDP, and a friend from Politics in Pubs. I spotted a lot of interesting things that chimed with my own interests, including a rejection of the so-called climate consensus and a decisive transition away from renewables. However, it wasn’t until I saw a very positive write-up by my friend David O’Toole that I realised it needed more serious attention.

As I began reading the green paper again, I had expectations about the likely strategy that it was going to describe. I knew it has a strong preference for public ownership and control, over the free market approach. However, as I read further, I realised that the authors had gone much further than a simplistic ‘public good vs private bad’ argument. Instead, it turned out to be a comprehensive discussion of a radically different approach to energy supply, albeit leaving me with lots of questions.

Different sections raised concerns, but I find most of these were addressed in subsequent sections. It’s a challenging read overall, but well worth it. I found myself agreeing with most of the ideas presented with the exception of the ‘Energy Credit’ system which underpins the whole strategy. It’s not that I disagree with the vision of Energy Credit as presented, it’s more that as a non-economist, I was left with lots of questions. I am fairly certain I won’t be the only one in this position. It left me feeling a bit like the time I tried to understand Modern Monetary Theory! The Energy Credit system is, however, a tantalising idea and it needs further discussion.

As a Reform UK party member, I don’t see any obvious differences in the proposals for the ways in which energy should be generated in future – particularly the welcome phasing out of renewables. What this paper provides is a radically different framework for how the overall energy system is managed. If we accept that market forces are not working, then there does not need to be any contradiction between the two parties’ policies. Both want cheap, reliable energy to take the pressure off hard-pressed families, to galvanise the economy and to kick-start an industrial and manufacturing renaissance.

Reform should take this paper seriously.

Getting into the detail

Overall Summary

The underlying premise in the paper is that we have an energy crisis that began in the early 1990’s when we replaced a planned state energy system with a free market system. The new system should have led to more competition and lower prices. In the end it led to the neglect and early closure of perfectly working fossil fuel power stations with many years of economic operation ahead of them. From the summary:

Without a planning and coordination authority, there has been no body able to veto a catastrophic experiment that began in the 2000s: the shift en masse to intermittent renewable generation.

The SDP is talking about the demise of the Central Electricity Generating Board (CEGB), established in 1957 through the Electricity Act, a nationalised monopoly owning almost all power stations and the high-voltage transitions network. It was self-regulating, so no need for an OFGEM, and parliamentary scrutiny occurred via questions to the Minister and review of annual reports. The CEGB’s income came through selling wholesale electricity to regional Area Boards, a process approved by the Minister of Power. A key aspect of its financial model was that it was operated on a ‘statutory corporation model’, which meant it had to be financially self-sufficient but not to the extent of maximising profits. Instead, surpluses were invested in new plant or to repay debt.

The summary goes on:

To resolve this, we propose an emergency ten-year plan to fix Britain’s generation mix and dismantle the energy rationing system. To do this, we shall create a new vertically integrated state-owned energy monopoly named “Central Energy.”

I like the idea of declaring an emergency as it clears the way for all sorts of remedial action, that otherwise might be blocked by established agreements and contracts. However, run by government, how do we prevent such a body being mis-directed by a future government more focussed on ideology than economics?

The summary outlines a fixed price of 10p for a kWh of electricity based on the introduction of an energy credit system. This is the most challenging proposal in the paper, and the one I am still struggling to fully grasp.

Part 1: Britain’s Energy Crisis

Part 1 of the green paper provides the overall rationale for why we cannot go on as we have been doing. I have written extensively about the direct costs of Net Zero policy as highlighted by Kathryn Porter (in the order of £220bn since 2006) and the OBRs assessment of Net Zero (adding £30bn annually to public spending). However, although it’s intuitively obvious that expensive energy will hit productivity, the SDP’s analysis is the first to highlight the extent of the problem in quantitative terms.

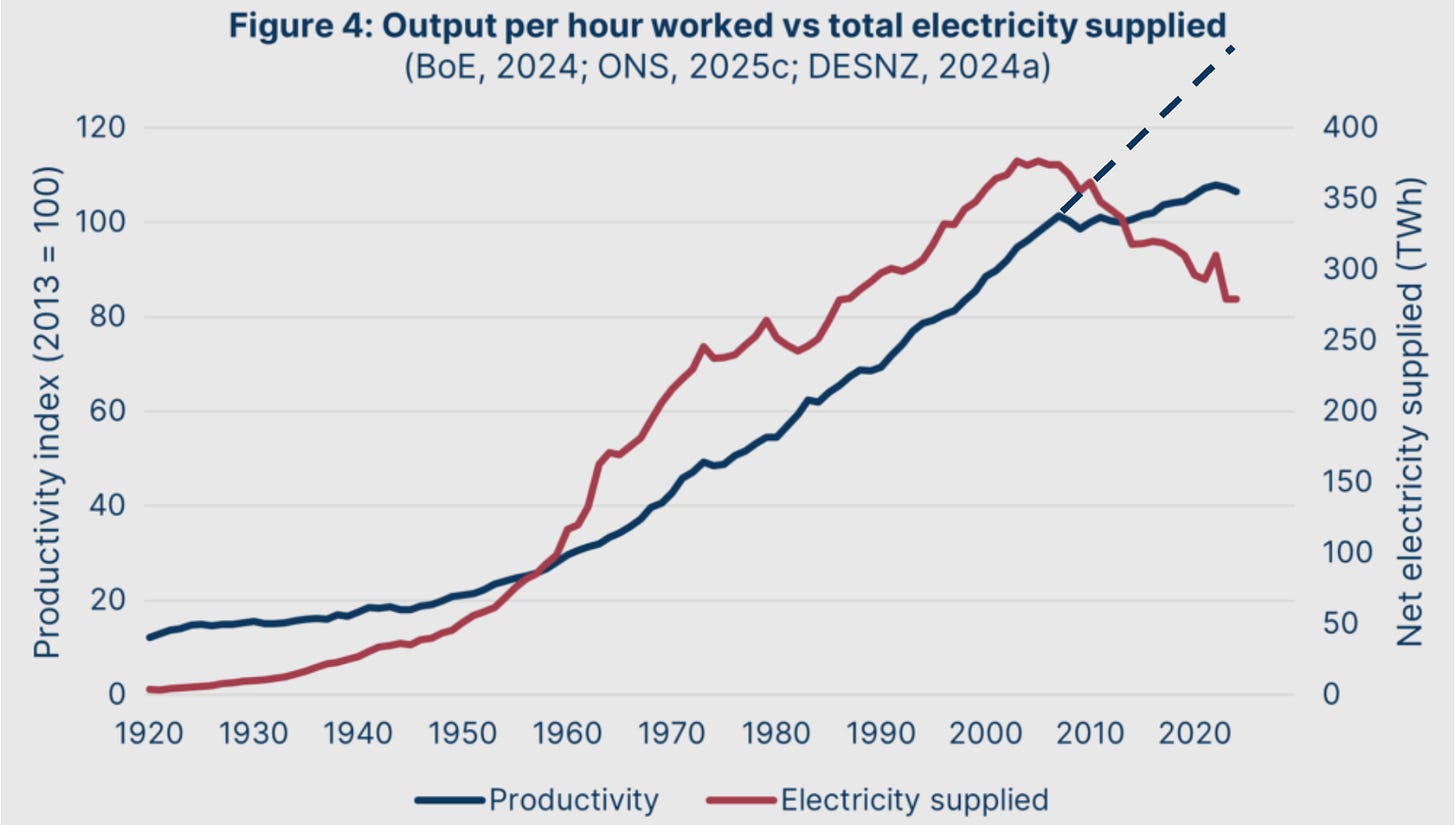

Figures 4 demonstrate the problem in starkly (I have overlain what might have been the projected growth from 2005):

We can see the impact of the new energy policy which has reduced consumption whilst stunting historic growth:

Between 2004 and 2024, rising energy prices have cost Britain an average of £146Bn every year in lost output. Total lost output stands at just over £3,070 billion, or £3 trillion – over a full year of output in 2025, or the equivalent of the full balance of the government debt.

It is no surprise therefore that “this tremendous cost has been felt in every facet of our lives”. There is a lot more detail but it’s hard to argue with the conclusion that our energy policy “has been most ruinous error in British economic history.”

Part 2: The Causes of the Crisis

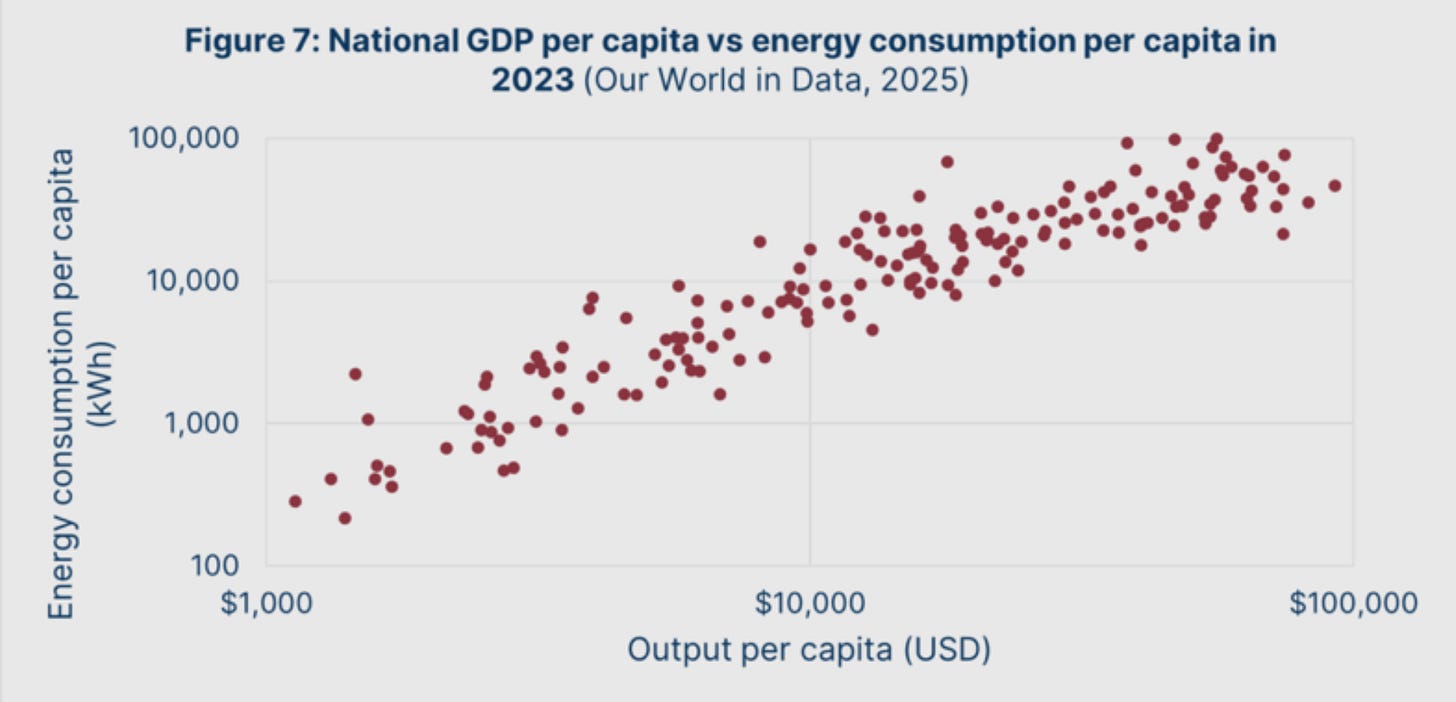

Part 2 kicks off with an important chart, highlighting the relationship between wealth (measured in GDP per capita) and energy consumption.

There should be no surprises here; richer countries consume more energy and vice versa. Correlation isn’t always causation, but this paper makes a strong case that has been highlighted previously by other commentators, such as David Turver. Therefore, if we make energy more expensive so that we use less, as has been happening, it should come as no surprise that we are get poorer.

The paper goes on to examine the nature of the grid system being an effective monopoly with the danger that this reduces incentives to innovate and be efficient. Secondly, customers are disconnected from generators via suppliers, who thus can profit in the process. Thirdly, power generation requires long term finance, which can be made more affordable by further development and refinement of current power plants.

The paper makes a strong case for long term public finance being cheaper than private debt. However, I wonder about who bears the risk. Private finance costs significantly more on paper. Think Private Finance Initiatives (PFIs) to build hospitals under Gordon Brown. But what happens when projects overrun when costs inevitably balloon, as in HS2 and just about all government contracts? We also have far more environmental legislation to fight through, and this will need tackling head-on.

Going into more detail, the paper discusses the break-up of the CEGB under reforms pioneered by Professor Stephen Littlechild of Birmingham University (via the Energy Act of 1989). Littlechild’s key concerns were about efficiency, incentives, monopoly/bureaucracy, and the need to introduce competition and regulatory frameworks in monopolistic utilities. The paper argues:

Littlechild was a sincere believer in the power of the profit motive at discovering efficiencies and cost reductions. In his view, once freed from political control, the energy system would dramatically improve by reducing the amount of capital tied up in underutilised infrastructure. Unfortunately, he was wrong.

The paper cites three reasons for why this new strategy failed:

The abandonment of planning

A flawed privatisation

The rise of renewables

My question at this point is how bad would the situation be now if 1 and 2 had not occurred and we were left simply pondering the impact of renewables? Look at this timeline for the way renewable energy policy has been developed:

1988 - Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) founded

1992 - UK signed the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) at the Rio Earth Summit

1990’s - Conservative governments (Major era) adopted an early, non-binding goal to reduce CO₂ emissions to 1990 levels by 2000 — mainly through the “dash for gas” (switching from coal to gas), which reduced emissions incidentally rather than through explicit climate policy.

1997 on - Under Tony Blair’s Labour Government, climate change became an explicit policy goal.

1998 - The Energy White Paper began linking energy strategy with environmental sustainability.

2003 - The Energy White Paper, “Our Energy Future – Creating a Low Carbon Economy,” was a turning point: “We are committed to cutting carbon dioxide emissions by 60% by 2050.” This was the first major UK policy document to make climate change the central driver of energy policy.

2005 - The EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) began, integrating carbon pricing into UK energy markets.

2008 - The Climate Change Act became the world’s first legally binding long-term emissions target (80% cut by 2050, later updated to “net zero” by 2050 in 2019). Established the Committee on Climate Change (CCC) to advise on carbon budgets. From this point, all UK energy policy had to align with carbon budgets — i.e., climate change became structural to policy, not optional.

2013 - Electricity Market Reform (EMR) explicitly reoriented the energy system to deliver decarbonisation, security, and affordability — the so-called “trilemma”.

2019 - Net Zero target (amendment to the Climate Change Act) made climate the overarching goal of energy and industrial policy.

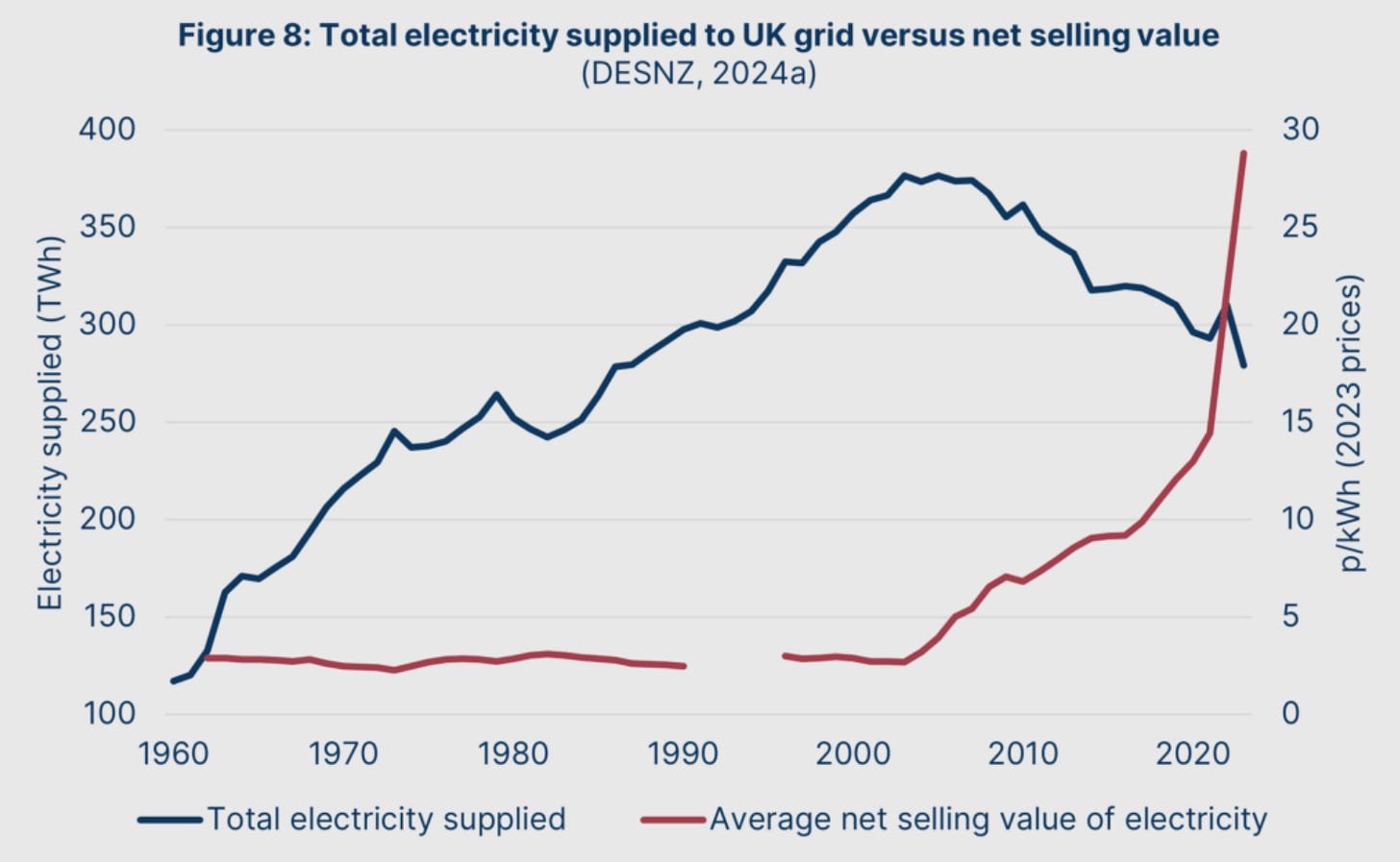

During this time figure 8 demonstrates how total energy supplied and net selling value varied:

This chart shows that energy supply continued to increase up to around 2005 and the average selling value remained flat until just before energy supply peaked. It cannot be coincidental that the imposition of climate goals coincided with, and drove, the dramatic rise in prices from around 2004. I.e. it is possible that Littlechild was correct, but we’ll never know. Who could have foreseen the dramatic impact of over-arching climate policies which would come to dominate energy supply?

The paper clearly illustrates the early demise of conventional thermal plants. I agree that we could and should have kept existing plants going, since the capital cost had already been invested and thermal plants have generally longer lifespans than gas plants. However, due to the pressure of growing climate “awareness” and the related policies, public pressure was galvanised behind the closure of “dirty” fossil fuel power stations. Therefore, I dispute the weighting given to the problems of loss of central planning versus a free-market approach and flawed privatisation, compared to imposition of climate policies.

Moving onto the rise of renewables, the paper points out the glaring contradiction that even as generating capacity has increased from 78GW in 2003 to 106GW in 2023, electricity supplied to customers has declined! How can this be?

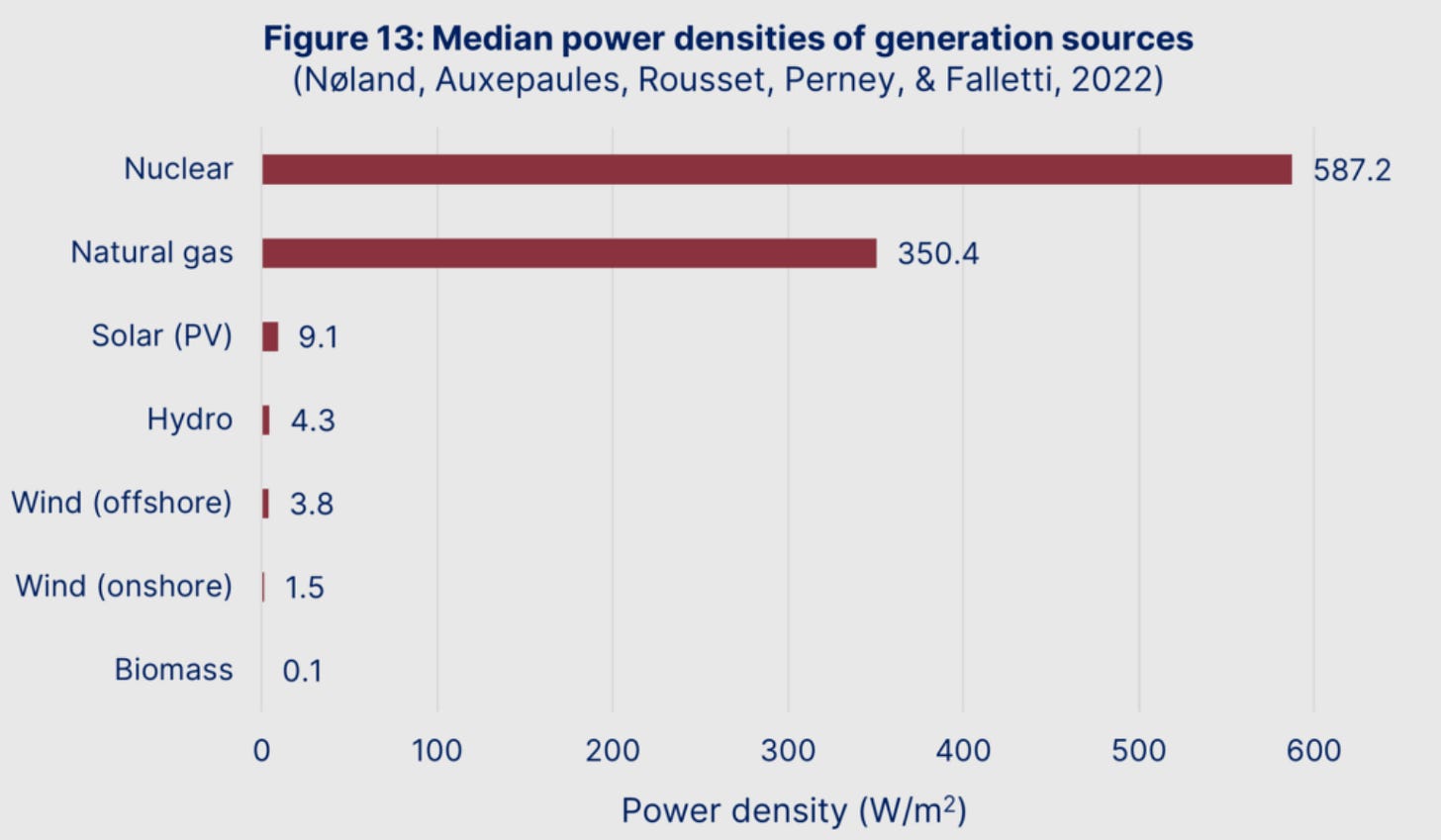

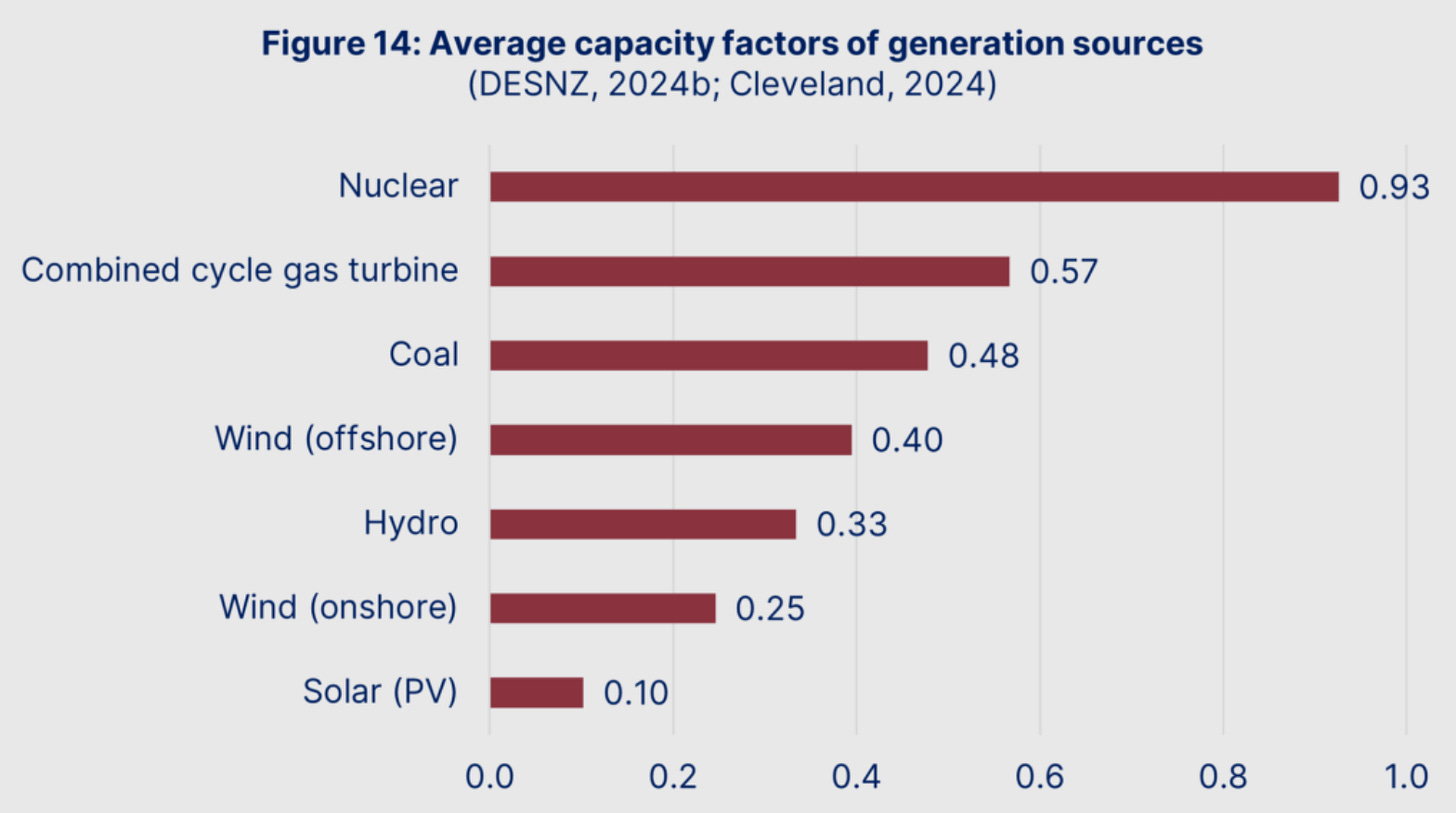

The answer is straightforward and is tied to energy quality which is a combination of power density and capacity factor. The former explains how much energy is output per unit area required, and the latter is the percentage of power delivered compared to the nominal power rating of a plant. Figure 13 in the paper shows a comparison between power densities of nuclear, gas and a range of renewable energy sources:

Figure 14 shows a similar comparison for capacity factors:

It should therefore be obvious why we can have more installed capacity than ever, but overall supply/consumption has gone down. And it gets worse! This simple comparison of capacity factors does not consider that, in general, availability of conventional power plants is managed by their operators (apart from breakdowns). However, renewable energy is governed by external factors such as wind speed and amount of daylight. Once these factors are considered, the so called ‘de-rated’ capacity factors are even less favourable for renewables.

When all this is considered, it is clear that:

…the main drivers of energy price growth in recent years have not in fact been wholesale costs. Instead, price growth is mostly due to rising policy costs, network costs, and capacity market mechanisms (wherein generation capacity is held idle for use in supply shortfalls).

The paper elaborates on how we have become a net importer of gas at the same time as carbon pricing has been imposed on gas supply. The latter adds something like 20% onto the wholesale price (I have seen much higher figures reported elsewhere) which is already inflated due to natural supply side shortages as we import more gas. This over reliance on foreign imports clearly exposed us to global price shocks as happened when Russia invaded Ukraine.

The paper also provides an excellent discussion of the problems arising from balancing supply and demand over a 24-hour period, with little to no grid scale storage. One particularly fascinating conclusion is that, according to Tong et al. (2021):

…even if Britain overbuilds three times more de-rated capacity than demand (assuming an optimal split favoured towards offshore wind), and also installs enough energy storage capacity to meet 12 hours of national demand, it will still need to have ready additional non-renewable capacity to meet up to 60% of demand throughout the year.

The sums required to make this work to meet current demand are eye-watering, for example £1,250bn for 2500GWh of energy storage! So, the next time someone says just use more batteries, explain what this will cost. And the paper goes onto explain that this is just the starting point, since storage like any other plant has a finite lifespan.

At this point the paper acknowledges the role of NESO as a planner, but rather than simply to increase supply and balance against demand, its role is to reduce demand:

The scale of this new planner’s ambition is truly monumental. NESO aims for a 54% reduction in peak demand by 2050 through a system of real-time “smart” tariffs.

I had never really appreciated that this was a central goal, and like the paper, conclude that what we are looking at is not ‘demand management’ but ‘rationing’. If I am late to this realisation as someone with an intense interest in energy policy, what are the chances that most people have no idea that this is going on?

Part 2 concludes with an excellent discussion on the spuriousness of many claims around climate, and concludes:

Atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations do not pose a risk to the biosphere itself even over an extended period of time

Sea level rises and extreme weather events cannot be expected to rise in an abrupt, linear manner

Humans have significant ability to offset and control the global climate system in response to greenhouse gas emissions

Britain’s own contributions to global emissions are causally insignificant

The full discussion is well worth reading and represents a welcome change from the SDP’s currently published official energy policy position which is:

We accept the broad scientific consensus that fossil fuels are contributing to climate change and that we need to reduce our aggregate usage of them

The paper goes onto to propose a variety of approaches to transition away from our current insane energy policy, most of which would be very difficult to square with their current position. This policy change is however consistent with Bill Gate’s recent announcement that rising carbon dioxide isn’t go to kill us. We could well be coming to the end of Climate Groupthink.

Part 3: A Ten-Year Plan

The paper then goes into detail about how we can fix the current system. The solution suggested is well-thought out, and leaves no stone unturned for generating baseload power, including fracking and even coal, though nuclear power will play a major role long term.

I found very little not to like here apart from a potential lack of recognition of the challenge to drastically reduce environmental legislation, particularly with respect to the construction of new nuclear. As I have written about previously, over regulation in this sector dramatically increase costs and construction times.

Part 4: The Energy Credit

I am not an economist, so I found this last section challenging. I suspect this means that in terms of communication – this will be the hardest part of the policy to get across to the general public by some margin. That said, this is what I came up with.

The energy credit is defined by a simple, unchangeable equation:

10 pence (p) will always entitle a bearer to 1 kWh of grid electricity.

The paper calls this a permanent nominal price fix.

For the average consumer:

This means that £1 will reliably buy you 10 kWh of electricity from the grid. On a day-to-day basis, customers will continue to have accounts and pay bills, but the pricing mechanism will be straightforward and guaranteed.

For the wider economy: The system is called the “energy credit” because it ties the inherent value of the British pound sterling directly to the provision of energy (and managed with the help of the Bank of England and the Treasury).

This fixed price is intended to reshape economic life, forcing the country to measure wealth and money in terms of its ability to enable productive work. I like the sound of that but the detail of how it would work in practice eludes me.

I asked AI for an analogy, and it came up with this:

The shift from the current market system to the Energy Credit system would be like moving from paying for water from a well (where the price fluctuates wildly based on rainfall and scarcity) to paying a fixed price for water piped directly to your house.

The state (Central Energy) guarantees that fixed price, but to honour that promise, it must ensure it continuously invests massive amounts of capital to build reservoirs, boreholes, and treatment plants (the new nuclear, gas, and coal capacity) so that the pipe never runs dry, regardless of the weather.

I can see that this makes sense, but it provides no guidance on how this integrates into monetary policy. And this is not just in terms of how the mechanism would work in the hands of the Bank of England. It is just as much about how this change in policy would be seen by the markets, with the potential turmoil that could occur. Managing this sort of transition will make Littlechild’s earlier reforms look like child’s play.

Closing Remarks and Questions

I welcome this green paper, which is a serious attempt to categorise the problem (a necessary pre-requisite to fixing it) and for proposing a detailed solution.

I don’t necessarily agree that it was the Littlechild reforms that set us off on our current path. Instead, I place far more weight on the impact of the switch to renewable energy. To be clear, the paper may be correct, I just don’t see the clear evidence in the data presented.

However, I do welcome the SDP coming to Reform’s view on not only the impact of Net Zero policy but also the use of flawed climate assumptions that underpin it.

I have lots of question, which I list here in no particular order:

Why 10p per kWh specifically?

How can the state guarantee this price forever, especially if global fuel prices or inflation rises.

If the price of energy is fixed, it will effectively become cheaper over time due to inflation, and presumably at some point it would be effectively free?

A related question, won’t this encourage more waste over time?

Alternatively, will this encourage more technology investment since the cost-of-capital reduces because energy is always a significant factor?

Why wouldn’t the price be impacted by major system failures, such as a nuclear power plant going off-line, or several if a major flaw was discovered in a specific reactor type?

If Central Energy is a monopoly, how can it guarantee a high-quality, efficient service? This is not something public bodies are well-known for.

Specifically, the Bank of England does not have a good record for controlling inflation. How would they perform better taking on the additional responsibility for adding energy to the monetary equation?

A state-controlled enterprise would be subject to future changes in government policy, whereas this strategy requires a long term multi-decadal commitment and stability. I.e., how do we prevent such a body being mis-directed by a future government more focussed on ideology than economics?

How do we overcome the government’s disastrous track record on major infrastructure projects, such as HS2.

How do we get people on board that believe that there is a climate emergency?

I hope this will be useful for anyone else getting to grips with Energy Abundance.

The SDP and Reform should have a meaningful conversation about this paper, because it provides the most serious analysis of the challenge to date. I am not sure whether it is practical to deliver, but there are so many good ideas here that it should not be ignored.

And why shouldn’t parties collaborate to fix a system that threatens to rear apart our country, as I recently asked Graham Stringer at a Battle of Ideas event?

We know the challenge will be immense. As two-party politics breaks down there is emerging a different politics with smaller parties at last gaining a significant voice. Amongst these is the Green party, who along with the Liberal Democrats, would fight these proposals just because they don’t fit in with their quasi-religiousbelief in a climate emergency.

We must be prepared, and to that end forging pragmatic alliances is key.